Sidewalk Compassion vs. Courtroom Reality (Part Two)

The Diversion Fantasy — and the Courts That Choke It to Death

Part One of this two-part series looked at the sidewalk — the place where illness is still recognized as illness, even when the public doesn’t know what to do with it. Now we move to the place where that recognition evaporates: the courthouse. Here, California’s “continuum of care” collapses into a narrow, brittle set of procedures that sound enlightened but operate like traps.

On paper, the state has already solved this problem. We have Mental Health Diversion. We have Behavioral Health Court. We have a legal framework that says people whose crimes grow out of mental illness should be stabilized, treated, and protected from the revolving door of incarceration. The Legislature passed these reforms with fanfare. Judges praise them from the bench. Prosecutors talk about them as proof that California is “doing something.”

But walk into an actual courtroom and watch what happens. The rhetoric quickly dies. And for those who need them most? These alternatives vanish the moment their “suitability” hearings are scheduled.

Paper Promises, Judicial Barriers

Mental Health Diversion was supposed to be the answer — not a miracle cure, but a path to a new start that would hopefully divert from the path to prison.

The Legislature didn’t hide its purpose. It put it right up front in section 1001.35: increase diversion, interrupt the jail-to-jail cycle, meet the unique treatment needs of people whose illnesses pull them into the justice system. That’s the policy. That’s the promise.

The very first stated purpose — before the procedures, rules, and constraints are even discussed in section 1001.36, state:

Increased diversion of individuals with mental disorders to mitigate the individuals’ entry and reentry into the criminal justice system while protecting public safety.

But as Prussian Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke might say, “Inside the courthouse, that purpose rarely survives contact with the enemy.”

The statute says the court may grant diversion. And “may,” in California criminal courts, behaves like a tripwire — a word that often gives judges broad discretion and gives prosecutors all the room they need to turn “treatment instead of punishment” into “not in this case”.

Appellate courts have spent the last five years trying to narrow that gap. Frahs opened the door. Moine said risk is defined narrowly. Williams reminded courts that “dangerousness” isn’t a vibe — it must mean a likelihood of a super-strike. Qualkinbush told courts they can’t hide behind rhetoric and must tie discretion to the statute’s actual purpose. And in 2024, Sarmiento finally said the quiet part out loud: relapse isn’t failure, drug treatment isn’t the same as mental-health treatment, and the Legislature meant what it said when it told courts to expand access, not contract it.

And still the trial courts resist. Especially in Fresno.

The fight in these hearings is never really about the statutory criteria — diagnosis, significance, treatment response, trial waiver, compliance, public-safety risk. Those are hurdles that can be cleared with evidence. The real fight is about judicial comfort. It’s about whether a judge trusts a program they cannot see, or a clinician they may have never met, or a treatment plan that does not fit neatly within the familiar boundaries of punishment.

So instead of the statute’s purpose, we get something else. We get judges treating relapse as proof of futility. Or delusional behavior treated as disqualifying because it “shows danger.”

This misses the whole point of Mental Health Diversion in the first place: to break the cycle of prison-to-street-to-prison-to-street. Almost every one of my mentally-ill clients who would benefit from MHD either avoids prison, or gets a short prison term with no treatment.

And then they’re back on the streets again.

So what’s more dangerous? Treatment that might break this cycle and ensure public safety? Or warehousing until the law requires us to release an untreated mentally-ill person back into the community?

Judges, of course, aren’t alone here (they’re just the final decision-makers). We also get prosecutors reframing symptoms as choices. They help the courts expand “dangerousness” into a catch-all concern, despite case after case holding otherwise. We get treatment plans rejected not because they are inadequate, but because they are unfamiliar and judges are not psychologists — clinical, forensic, or otherwise.

Ultimately, what the Legislature promised is not what the courts deliver.

Diversion hearings were supposed to be about medical need and public safety, with public safety defined exactly the way the statute defines it.

But in too many counties, these hearings feel more like probation interviews dressed up as therapeutic gatekeeping: What did you do before? How many times have you tried? Why didn’t you succeed? Doesn’t that lack of prior success — which I recognize left out some critical components the new plan includes — indicate a likelihood of failure?

Judges convert the very conditions the law was built to address — chronic illness, trauma, relapse, lack of prior treatment — into reasons to deny the relief designed for those exact conditions.

This is why the cases matter. They aren’t academic. They are roadmaps showing judges how far they’ve drifted from the law’s purpose, and how often they substitute instinct for analysis.

Sarmiento is a perfect example: the trial court denied diversion even after conceding eligibility, even with an unrebutted expert evaluation, even with a treatment plan the prosecution couldn’t dispute. The appellate court had to pull the judge back to the statute itself — the presumption of causal connection, the narrow definition of danger, the Legislature’s directive to expand diversion, not shrink it.

Too often, I argue — often unsuccessfully — exactly what Sarmiento said:

Reducing crime makes our communities safer, to be sure, but successful treatment also improves our society in a myriad of other ways by helping those with mental disorders become more productive citizens, to the benefit of their families, their employers, and the community at large. The trial court’s decision here failed to follow the Legislature’s direction to focus less on the flaws in Sarmiento’s past and more on the promise of her future and that of her community. Without that correction, diversion would exist only as an idea, not a remedy.

— Sarmiento v. Superior Court, 98 Cal. App. 5th 882, 897 (2024)

Without that understanding, diversion exists only as an idea, not a reality. Not a remedy. Certainly not the remedy the Legislature envisioned of treatment rather than warehousing.

Yet here’s the raw and unabashed truth: the gap between the Legislature’s purpose and the courts’ practice is not accidental.

The gap reflects the same institutional reflex that has always governed how California treats mental illness: sympathy at a distance, caution when a real person is in front of the court, and a willingness to let the system’s comfort take priority over the individual’s treatment needs. That gap is where people fall, and it’s where the system most reliably reproduces the very crises it claims it wants to prevent.

It’s the Sidewalk versus Courtroom that this article and my last have focused on.

Thwarted Dreams, Everyday Reality

“The idea of Mental Health Diversion is largely a legislative dream, and getting into it is a mental health sufferer’s judicial nightmare. Prosecutors and judges hate this law, and do everything possible to thwart the law, and to keep people out of Mental Health Diversion.”

— Rick Horowitz, I Had A Dream (February 2, 2022)

I wrote those words nearly three years ago, and the landscape has only hardened since. The Legislature’s dream hasn’t changed. The need hasn’t changed. The evidence hasn’t changed.

But the habits of the courthouse have deepened, calcified, and become more entrenched — especially here in Fresno, where the program exists on paper yet behaves more like a privilege the court bestows on a chosen few rather than a statutory pathway available to anyone who meets the actual criteria.

Judges still speak the language of caution more fluently than the language of clinical reality. Prosecutors still argue from police reports as though they were diagnostic instruments.

I had a case — years ago now — with a client who committed a type of crime that caused both the judge and the prosecutor to say he was not suitable for the program. I fought back with a legal brief that explained why he was. There was a specific carve-out for the crime of which he was accused. The prosecutor “vehemently” — I believe that was her own choice of word — objected.

But after I submitted my new brief directly addressing their — remember, the judge was against letting him in, too — reasons for rejecting him, the judge said, “Based on Mr. Horowitz’s brief, I don’t believe I have a choice.”

And my client got in.

And the prosecutor never stopped objecting to his presence at almost every review hearing over the next two years. On the day of his graduation, the prosecutor tried to argue he should not be allowed to graduate and have his case dismissed. Thankfully, the new judge agreed with me that he had already graduated by operation of law, and we were just formally recognizing that in the courtroom.

It has been, as I said, some years since that happened. My client has gone on to marry, build a family, and is a successful functioning member of society without any further criminal behaviors.

Yet the resistance continues. Indeed, it has deepened.

Counties still use “flexibility” to justify an absence of meaningful treatment options, even while pointing to those same options when they want to appear supportive of the law. And when I find those options outside the county’s purview — helping the client locate the treatment needed and find a way to fund it through insurance — we again see the reality behind the appearance.

But I am buoyed by the appellate courts which have now said explicitly what used to be implied. They’ve said the trial courts are misreading the statute, misapplying the criteria, and misusing their discretion. They’ve said relapse is not danger. They’ve said drug treatment is not mental-health treatment. They’ve said future promise matters at least as much as past failure. And still, at the ground level, the resistance persists.

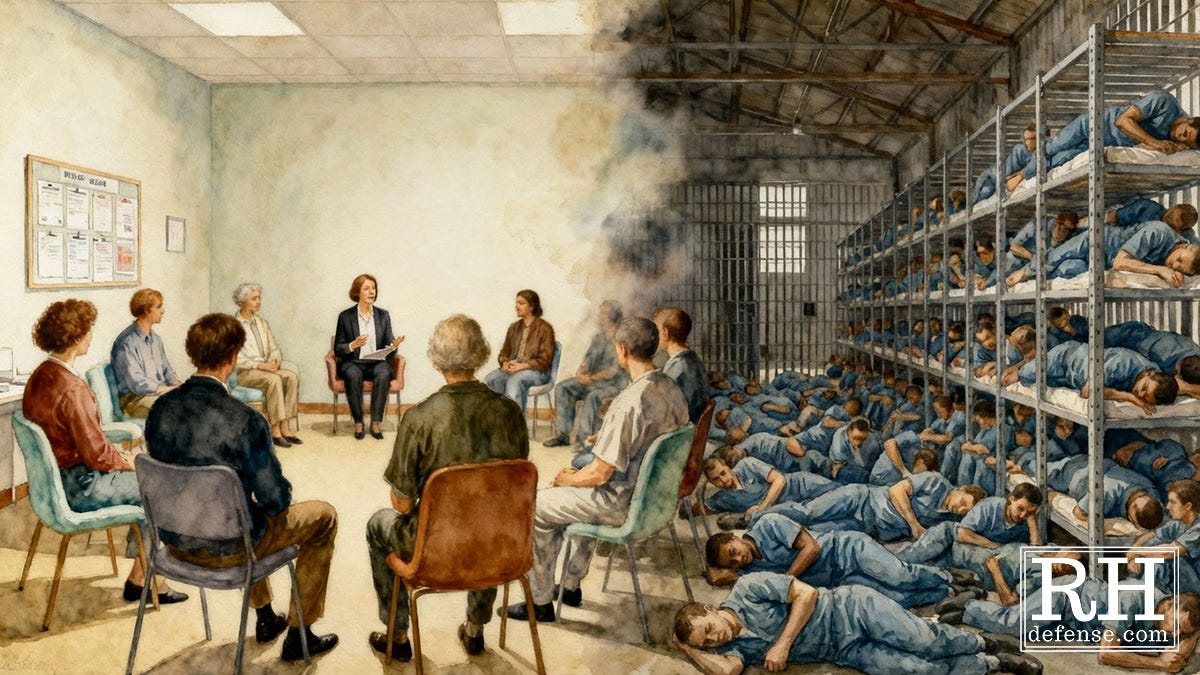

And that leads to the final, unavoidable point: what happens when the system chooses warehousing instead of treatment?

If you’ve watched this system up close — as a family member, defender, treatment provider, or court employee — what did you see? Please tell me in the comments. Your insight may help someone who’s facing the same barriers right now.

The Consequence No One Talks About

I used this quote in I Had a Dream and it’s worth repeating here:

When researching mental illness and incarceration, one very startling statistic pops up: 1 in 5 people currently incarcerated in jails or prisons across the United States are living with a diagnosed mental illness. When one looks at the juvenile justice system, the numbers grow even more staggering, with a whopping 70% of kids going through the system having some form of mental health problem. What does this mean for those with mental illnesses going through the justice system? Rather than getting the proper care they need, they will instead be in a place that will more than likely continue to worsen their condition.

— National Alliance on Mental Illness, Mental Illness is Not a Crime (Undated)

NAMI is right. And those numbers aren’t abstractions. They’re the people we see at arraignments every day — human beings — people courts declare “unsuitable” not because the law bars them, but because their illnesses make the case harder to manage, harder to predict, or simply harder to fit into the court’s comfort zone. And most of them are not being shipped off to long prison terms where some mythical treatment program might exist. They get county jail terms, or probation with jail time, or short prison sentences that amount to little more than warehousing.

I had a case — again, many years ago now — where the situation I worked out meant that my client would spend more time locked up in a secure treatment facility than he would have spent in prison. But instead of being warehoused, he would get the treatment for his drug addiction and mental illness issues. The client was agreeable to the arrangement even though he was well-informed that he could get out of custody faster if he did not agree to the program.

The prosecutor and some families of the alleged victim (nobody was hurt in the case; just said to be scared) objected. I don’t remember if they objected “vehemently”.

Fortunately, the judge in that case recognized what I successfully argued then and frequently unsuccessfully argue now: he’s going to go to prison for a while and then our community would get him back.

And at the risk of the redundancy because it highlights the absurdity of the objections: he was going to be locked up longer under the treatment plan than he would have been if he were only warehoused in prison without treatment.

So these are our choices: Treatment or not treated. Stabilization or not stabilized. Safer or not safer.

Taking the latter of each of those choices means my clients return older, more traumatized, and further disconnected from the families, employers, and neighborhoods the courts say they’re protecting.

This is the part no one in the courthouse says out loud. Untreated mental illness doesn’t pause itself during incarceration. Jail is a temporary waystation — as I’ve called it, a place to “warehouse” mentally-ill individuals who because of their mental illnesses, commit crimes. Maybe self-medicate by using street drugs.

But jail is not benign. Jail is a catalyst — and not the kind that creates something better. When someone in crisis is denied treatment because a judge or prosecutor finds the case “too risky,” we guarantee a future encounter with the same untreated illness, the same destabilization, the same cycle.

The Legislature wrote a statute to interrupt that cycle. But courts apply it in a way that ensures it never ends.

That’s the real divide between sidewalk compassion and courtroom reality. One space sees a person in crisis; the other sees a problem to be managed. Until judges are willing to follow the law as written — to honor its purpose and trust treatment over warehousing — California will keep manufacturing the tragedies it claims to be trying to prevent.