Sidewalk Compassion vs. Courtroom Reality (Part One)

We’re tired of letting people die — unless we put them in a jumpsuit first

In this Atlantic piece, a man lies in the street in San Francisco, trying to die. Paramedics know him. Hospitals know him. Everyone knows him, because they all see him over and over — revived, released, returned…untreated. That’s the cycle California calls “compassion”.

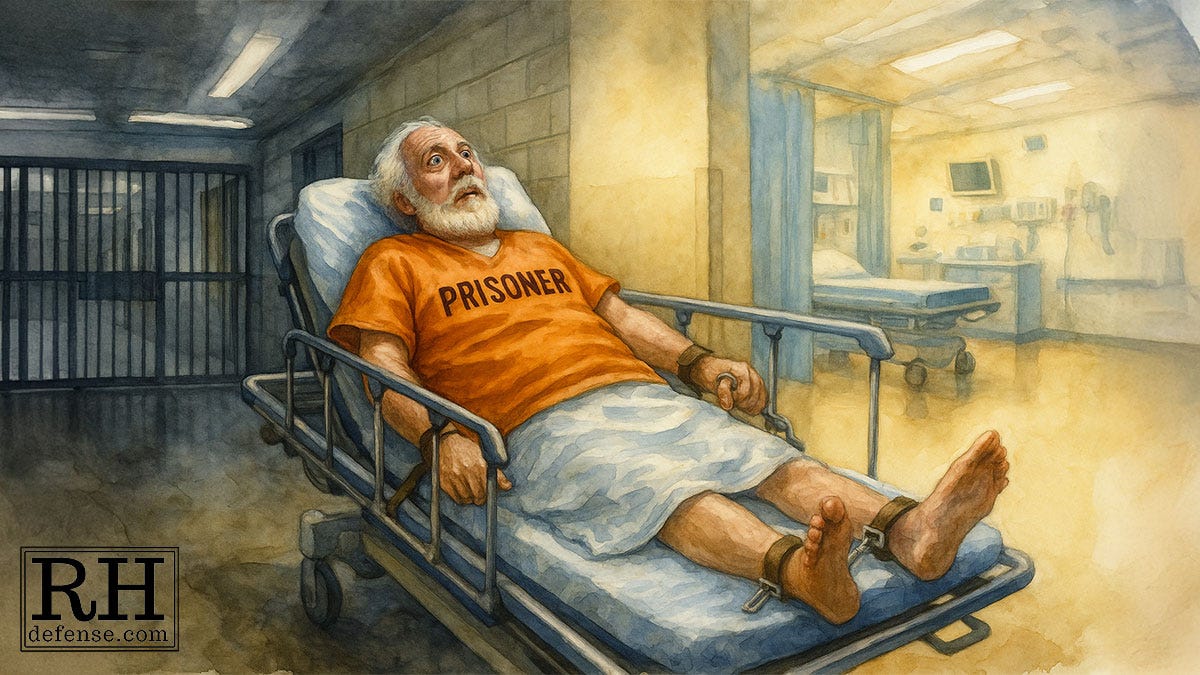

I meet men like him only after the cycle ends, when the street gives up and the courtroom takes over — and suddenly the same psychiatric agony becomes “willful misconduct” and wears a yellow jumpsuit. (Orange is the norm. As in Orange is the New Black.)

California tells a simple story about mental illness in public spaces: these crises are tragedies we witness as we step around, not failures we create. So the policy conversation stays focused on sidewalks, storefronts, transit stops — and on what to do with the people whose suffering is too visible to ignore. That’s where words like “compassion,” “care,” and “urgency” get used.

But walk a few blocks into any courthouse, and the vocabulary changes instantly. The same behaviors that elicit pity in the street are reclassified as choices, threats, or moral defects the moment a charging document appears.

We pretend the issue is where these people sleep, or whether they accept treatment, or whether police and paramedics can “intervene” sooner. But the real divide isn’t geographic — it’s philosophical.

On the sidewalk, mental illness is framed as a humanitarian emergency. In court, it’s framed as a disciplinary problem. And between those two worlds is a chasm we built on purpose: a system that abolished the old asylum model without ever creating the community-based care that was supposed to replace it — leaving jails and prisons to become the new warehouses for people whose only crime is being sick in public.

The Myth of Progress After the Asylums Closed

We congratulate ourselves for shutting down the old state hospitals and pretend that this marked some moral evolution.

The public story is that we ended cruelty. The real story is that we ended one kind of confinement and quietly replaced it with another. The institutions that closed were abusive, but the cure never arrived. The community treatment system that was supposed to follow never materialized. Funding evaporated. Promises faded. People with serious mental illness were pushed out of the locked wards and sent into a world that had no plan for them.

What filled the vacuum were the streets, the emergency rooms, the jails.

The state closed the doors of its hospitals and then handed the problem to agencies that were never designed for treatment. Police became first responders for psychiatric collapse. Jail cells became holding tanks with an occasional “5150” commitment that could serve as a Badge of Honor if the “5150” individual was later sent to prison. (Some inmates even got “5105” tattooed on their faces as a warning to other inmates.)

Prisons became long-term storage.

We did not create a humane alternative to the old institutions. We created something rougher and more chaotic, and we act as if the change is progress simply because the buildings look different and people who would otherwise have been forced into treatment programs are “free”.

But inside a jail (or prison), suffering is not met with care. It is met with orders, lockdowns, solitary confinement, and a constant struggle to survive an overcrowded environment (when not in solitary, suffering delusions brought on by the sensory deprivation).

Vulnerability draws exploitation. Symptoms turn into rule violations. Treatment, if it happens at all, is reduced to quick assessments and inconsistent medication. The people who need the most help end up in places designed for punishment. And the state points to the closed hospitals as proof that it values compassion.

What Jail Does to People Who Are Already Sick

The people who cycle through these systems are already fragile when they arrive. Jail takes whatever stability they have left and strips it away.

Jail is loud, unpredictable, and built around compliance instead of care. Someone in the middle of a psychiatric break is expected to follow orders he can barely understand. When he can’t, the response is punishment.

Not treatment. Punishment.

A person hearing voices is written up for failing to respond to the voices he did not hear. A person terrified and confused is labeled aggressive. A person who withdraws into himself is marked as defiant.

Officers rotate through shifts. Clinicians rotate through caseloads. The person at the center of the crisis stays trapped inside a structure that sees his illness as a security problem rather than a medical one.

Nothing about this is designed to heal. It is designed to contain.

Most people outside the system never see this part. They see the sidewalk. They see the dramatic crises in public. They don’t see the hundreds of quieter collapses that happen behind locked doors. And they don’t see how often the court system takes someone who should be treated and instead funnels him into a place where every symptom becomes grounds for discipline.

A Short Reality Check

We like to pretend this is a problem limited to a handful of people we see on the street.

It isn’t. The numbers tell a different story.

Roughly one in five adults in the general population has a mental illness. In jails and prisons the figure is closer to two in five, and the rate of serious conditions like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder climbs even higher. The crisis that dominates the sidewalks is only the visible part. The larger crisis is inside the walls, out of sight, where the system keeps insisting it is dealing with criminals rather than with people who are sick.

If you’ve seen these failures up close, I’d like to hear your experience. Part Two is coming soon, and your stories shape it.

The Appeal of Sidewalk Compassion

People respond differently when illness is out in the open. A man screaming at a bus stop is uncomfortable to watch, but most people recognize something is wrong. They may step around him or call someone else to handle it, but they still see a person in distress. They see a crisis. They see a life unraveling in real time. The behavior is frightening, but it is still read as a symptom.

That sympathy evaporates once the same person is arrested. The public imagination splits neatly in two. On the sidewalk he is sick. In custody he is dangerous. The illness didn’t change. The setting did. And once he enters the courtroom, the system treats his collapse the same way it treats any other disruption: as a failure of character rather than an emergency that never received help.

California’s leaders understand this difference in perception. That is why the debates about what to do with the “hard cases” rarely focus on what happens after arrest. They focus on the street. The freeways. The storefronts. The visible spaces where the public wants something done. And they frame it as compassion, even when the next steps are more about containing people than treating them.

The Conservatorship Continuum

The state talks about a “continuum of care” for people in psychiatric crisis. The Atlantic article goes heavy on this because it sounds thoughtful and humane. Voluntary services for those who accept them. Short-term holds for those too lost in their illness to make decisions. Long-term conservatorships for the few who cannot survive without someone stepping in. It is presented as a spectrum of compassion.

When the ambulances hit the road it is little more than a spectrum of control. Voluntary services are thin and scattered. Crisis beds are limited. The holds cycle people through hospitals that cannot keep them. And conservatorship has become a political talking point instead of a functioning path to stability. The public sees it as intervention. The people caught in it experience it as another version of confinement, only with paperwork instead of razor wire.

The whole structure exists to reassure the public that something is being done. It is supposed to be the humane alternative to criminalizing mental illness. But the reality is that it often runs parallel to the criminal system rather than replacing it. People bounce between both tracks, and when one track fails to “fix” them quickly enough, the other steps in with handcuffs.

In short, they get railroaded so we get peace of mind.

The Funnel That Follows

By all appearances, the sidewalk gives people a kind of sympathy the courtroom never does. The conservatorship system is built around that sympathy, even when it can’t actually deliver what it promises. But once a person crosses from the sidewalk into the justice system, the options shrink. The same person who was a public health problem on Monday becomes a public safety problem on Tuesday, and the system treats those two roles as if they belong to different human beings.

The funnel is simple. Behavior that looks like illness in the street becomes misconduct in court. Misconduct becomes a violation. Violations become custody. And custody becomes the new institution we pretend we no longer have. It is not a continuum of care. It is a narrowing path, and it ends in the place least capable of helping anyone.

Where This Leaves Us

This is the part of the system most people never think about. We argue about sidewalks and tents and storefronts. We argue about treatment beds and conservatorships. We argue about what compassion should look like in public view. We almost never talk about what happens once the same person is pulled into the justice system and treated as if his illness were a moral failure.

California built alternatives to jail for people whose crimes grow out of mental illness, and those alternatives aim to keep them out of the funnel entirely.

In practice they are rare. In some counties they are almost mythical. Judges resist them. Prosecutors fight them. And the people who need them most are the same people least likely to be offered them.

Part One has looked at the Sidewalk. Part Two will look at the injustice system and those supposed alternatives to untreated incarceration. Mental Health Diversion. Behavioral Health Court. The tools that exist on paper but are withheld in practice. If the state is serious about compassion, this is where the shift hits the fan.

If you’ve seen these failures up close, I’d like to hear your experience. Part Two is coming soon, and your stories shape it.

I was struck by this: "Roughly one in five adults in the general population has a mental illness. In jails and prisons the figure is closer to two in five, and the rate of serious conditions like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder climbs even higher." What a broken mess.

Incredible. Thank you so much for writing this. Looking forward to the next installment. <3