There Are Not Two Sides

Criminal Defense Lessons Learned from the Market

If you’re a regular reader, it won’t surprise you that I recently started enjoying day trading. In fact, I still owe two more parts to my four-part series on plea bargaining.

Today’s post is another of what I guess I’ll call “interjectory posts” because, as I mentioned in Part 1 of the four-part series, my ADHD and the flow of events means that I’m interrupting my four-part series at times by interjecting what’s caught my attention at the moment.

But we’re still kind of on what’s become a recent theme: criminal defense lessons learned from the market.

What has surprised me is how often I hear an echo between trading and criminal defense. Insights from the market bleed into what I already know about defending people in court; things I’ve learned over years of criminal defense practice turn out to be unexpectedly useful when I’m looking at charts.

This piece grows out of one of those echoes. It’s about what day trading reinforced for me — not about how to trade, but about what not to focus on — and why the same mistake shows up over and over again in criminal cases.

We Are Storytelling Animals

We are storytelling animals. We can’t help it. When something happens — a crime, a price move, a candle on a chart — we reach for a story that makes it make sense. Stories are how we organize experience. They compress uncertainty. They give us the feeling of understanding.

That instinct is usually harmless. Sometimes it’s useful. But in two places I spend a lot of time — criminal courtrooms and financial markets — storytelling becomes dangerous. Not because stories are always false, but because they move faster than evidence. They fill in gaps and smooth over missing steps. They make conclusions feel earned long before they’re justified.

This is why the “both sides of the story” idea is wrong.

In a criminal case, there usually aren’t two stories. There’s one story — the prosecution’s — and the problem is not that the defense needs a better one. The problem is that the story itself is doing work the evidence doesn’t support.

A good defense attorney doesn’t usually replace that story with another.

They do something more subversive.

They interrupt.

There Are Not Two Sides

“Both sides of the story” is one of those phrases people reach for when they want to sound reasonable.

It assumes symmetry. Balance. It assumes that a criminal case is a disagreement between two competing narratives, and that justice somehow emerges from weighing them against each other. That framing is comforting. It is also wrong in a way that matters. Because this is not “adversarial” — which is what makes our system work — but turns it into an ordinary debate.

In fact, I often laugh when listening to prosecutors argue in court. It always reminds me of a high school debate and every word is predictable. They just have to say it for the record as the judge nods along; the judge’s decision was already made. The prosecutor will usually win. But the debate format must be maintained so that it sounds like there were reasons for not following the law.

And this happens because, in a criminal case, there usually aren’t two stories, but judges, prosecutors, and even defense lawyers fall into the trap of believing there should be.

Yet, there is one story — the prosecution’s. They are making accusations. They do so using stories that may or may not be veridical.

Those stories arrive early and confidently. They have arcs. They explain behavior, assign motive, and give meaning to ambiguity before the evidence has done much work at all. Once that’s in place, they start doing what stories always do: fills gaps.

Too often it’s pure confabulation.

And just like what we see when LLMs confabulate, what gets called “evidence” in this context often isn’t evidence in the strict sense. It’s inference presented with confidence. It’s interpretation treated as observation. It’s narrative momentum doing work that proof hasn’t yet earned.

This is why the “both sides” idea misdescribes the defense function.

The distinguishing move is interruption.

The defense is not there to tell the other side of the story. Sometimes a defense narrative is useful, even necessary, because jurors want sequence and coherence. But that is not the heart of the work, and it’s not what distinguishes good defense lawyering from bad.

The distinguishing move is interruption.

A good defense attorney slows the story down. They resist its pull toward inevitability. They keep pointing back — quietly, persistently — to what the evidence actually establishes and where it stops. They don’t rush to replace one explanation with another. They make the gaps visible.

That is often unsatisfying. Stories promise understanding, and interruption denies it. But understanding is not the legal standard. Proof is — at trial it is proof beyond a reasonable doubt. And proof does not improve just because a narrative feels complete.

What I said about machines in The Mirage of Reasoning Machines: The danger of trusting computer-generated charisma over proof is equally true about the prosecution’s story:

Truth is what courts are supposed to trade in. But “truth” becomes slippery when a machine can unspool an elegant paragraph that looks like logic and sounds like logic, yet collapses the moment you take it out of its comfort zone. That collapse—the gap between sounding right and being right—isn’t a quirk. It’s the core of the computational claim.

This is why there are not two sides. There is a story that wants to carry the case to a conclusion, and there is the work of refusing to let that happen without support.

That refusal is not properly viewed as obstruction. It is the job of a criminal defense lawyer.

What the Market Reinforced

Day trading has a way of punishing you quickly for paying attention to the wrong thing.

If you spend your time trying to explain why a stock moved instead of noticing how it moved, the market has a way of correcting you. Not philosophically. Financially. You can tell stories all day long. The chart doesn’t care.

A lot of trading books quietly encourage the wrong habit. They talk about what “buyers want” or what “sellers are trying to do.” They describe candles as expressions of intention. Fear. Confidence. Hesitation. Capitulation. Even the basic vocabulary — bullish, bearish — is psychological shorthand. We’re stuck with it now, but that doesn’t make it accurate.

The truth is simpler and less satisfying.

In the market, we don’t know what anyone wants.

We don’t know why a buyer bought or a seller sold. We don’t know what they were thinking, what they hoped would happen next, or whether they even meant to be there. All we actually know is what happened. Price moved. Volume printed. A level held or failed. A candle formed with a particular shape.

Everything else is projection. Made-up stories that add unnecessary — and misleading — cognitive load.

Markets are full of such ready-made narratives if you want them. Every candle can be given a backstory. And if you listen to enough commentary, you start to believe that understanding those stories is the same thing as understanding the market.

It isn’t.

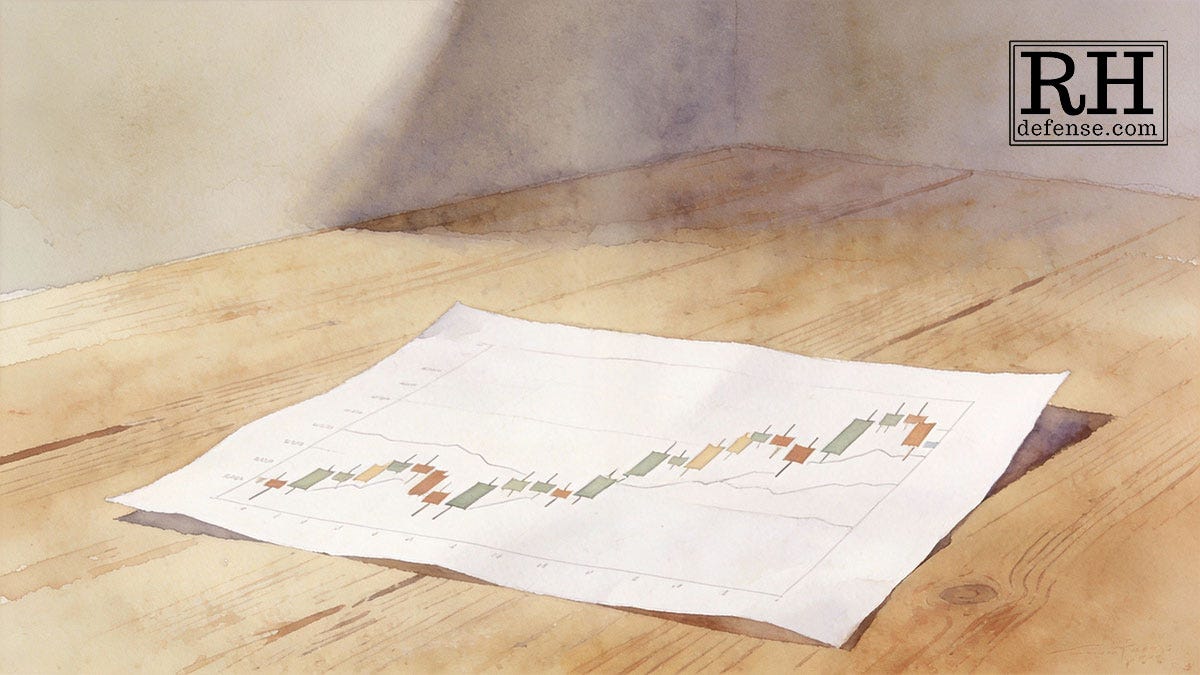

What matters are patterns. Shapes. Repetition. What tends to happen after certain configurations appear, and what tends not to. The chart records outcomes, not intentions. Indicators summarize what already occurred. They don’t tell you what anyone wanted; they tell you what actually happened.

I don’t like upper wicks. Especially long ones. I don’t care what emotional state produced them. I don’t care whether a book tells me they reflect hesitation, profit-taking, or hidden strength. I know what tends to happen after I start seeing them. That’s enough.

Trying to interpret the psychology behind the candle slows you down. It opens the door to rationalization. Maybe this upper wick doesn’t mean what upper wicks usually mean. Maybe the story explains it away. Maybe you should give it one more bar to complete the tale, fill in one last missing gap.

That’s how bad trades linger.

The discipline trading forces on you is not insight. It’s restraint. You learn to stop letting explanation substitute for pattern recognition. You learn to accept that a configuration can be unfavorable even if you can tell a perfectly coherent story about why it shouldn’t be.

That lesson carries over cleanly.

In court, explanation creeps in the same way. The prosecution offers a story about what someone “must have wanted,” what they were “trying to do,” what their behavior supposedly reveals about their inner state. This is how they want you to (mis)judge ordinary non-criminal behavior to get to a conviction. Intent and motive fill gaps. Coherence replaces constraint.

Just as in the market, the danger isn’t that the story is implausible. It’s that it feels plausible enough to stop questioning. That’s why juries embrace the prosecutor’s stories.

We all crave order. When the world tilts toward chaos — whether it be politically, technologically, or personally — certainty feels like a handrail. A calm, authoritative voice can do more to settle nerves than any mountain of evidence.

— Rick Horowitz, The Sound of Certainty: How We Mistake Confidence for Truth (November 10, 2025)

Trading reinforced something I already knew but had started to take for granted: explanation is often just latency. It delays the moment when you’re supposed to notice that the pattern no longer fits. And by the time you’ve finished explaining, the opportunity to act — or to interrupt — has usually passed.

In both places, the work is the same. Stop the story. Look at what’s actually there. Notice where the pattern breaks.

And don’t talk yourself back into it.

We Interrupt This Story To Look at the Facts

I’ve spent most of my professional life interrupting stories.

Not replacing them. Not competing with them. Interrupting them before they harden into something that feels inevitable simply because it’s been told smoothly enough times.

“Let’s look at the facts,” I say. “Because the story you just heard is just that: a story.” The prosecution, we might say, read the candles, saw what was printed, and jumped into thinking he knew what the buyers and the sellers were up to.

Day trading didn’t teach me that. It reminded me of it. The market is just less patient than a courtroom. It doesn’t wait for you to finish your explanation. It doesn’t care how elegant your story is. It responds only to what actually happened — and to what tends to happen next.

Courts are slower. More ceremonial. More tolerant of confidence masquerading as proof. But the danger is the same. When explanation outruns evidence, when coherence substitutes for constraint, when a story does work the facts haven’t earned, the result isn’t understanding.

It’s error. A false conviction. An accused person’s liberty — and often family, home, job, sometimes life — is taken away from him.

That’s why interruption matters. Not as a rhetorical move, and not as obstruction, but as a refusal to let narrative charisma stand in for proof. In trading, that refusal keeps you from lingering in bad positions and losing money. In criminal defense, it keeps people from losing their liberty because a story sounded right.

There are not two sides.

There is a story — and there is the discipline of stopping it at the point where it stops being justified.

That discipline is the job.

I always learn something from Rick. This piece is no exception. The parallels he identifies here are paradigms that can help any trial lawyer to be more effective.

For those folks who haven't read your pieces on trading, would you please provide some insight into what a "candle" is in the trading world? Maybe a link or two to explanatory websites?