Testimony, Revisited

On the Gap Between Recognition and Reality

I’ve been called a lot of things in my life. But this morning, after court, was a new one for me.

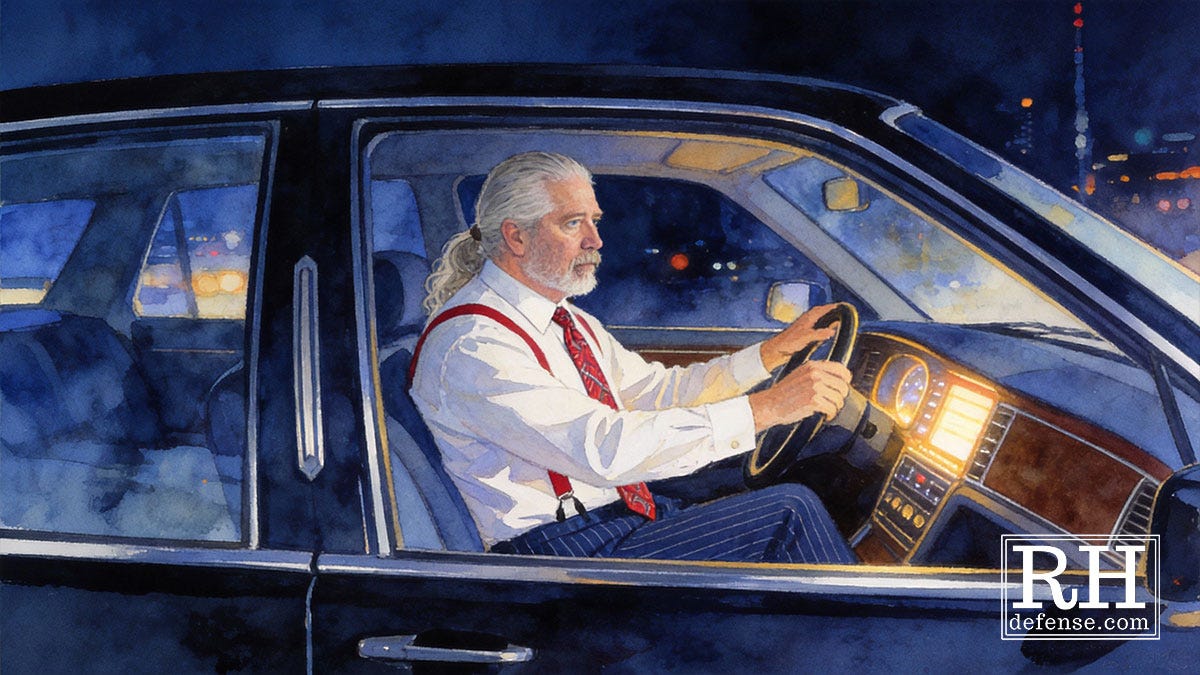

I was standing with a client’s family — a large one, the kind you mostly see in hallways and parking lots, faces you learn by proximity rather than names — when one of the men looked at me and said, “You’re just like the Lincoln Lawyer.”

I knew he meant it as a compliment. I also knew, immediately, that I didn’t know how to receive it.

I’ve seen The Lincoln Lawyer. I remember the outlines: a defense lawyer working out of his car, relentless, present, human. That was enough to understand what the man was trying to say. Court moved on. The day moved on.

That night, the same thing happened again.

Someone I’ve known for a while now sent a short message relaying a comment from her husband:

My husband just called you Mickey Haller. He really likes the fact that you are like the Lincoln Lawyer. 😂

Same reference. Same day.

I noticed the repetition. I didn’t know what to do with it yet.

This piece is about why a comment meant as praise can land uneasily — and what that discomfort says about the way criminal defense is practiced now.

When Praise Stops Making Sense

The discomfort wasn’t about modesty, and it wasn’t about self-doubt. It was about fit.

Praise assumes a certain alignment between effort and outcome, between judgment and reward. It assumes that the kind of work being praised still makes sense inside the system as it actually operates. That assumption no longer holds.

The version of criminal defense lawyering people recognize — the one they still reach for when they’re trying to describe presence, relentlessness, or care — depends on conditions that are increasingly rare. Time. Discretion. Negotiation. The ability to slow a case down long enough for facts to matter.

I often tell clients that part of my job is to drag the case. Judges don’t like it. Prosecutors don’t like it. Sometimes clients don’t like it either — which is why I explain this at some point. I don’t do it with every case; not every case needs that. Some cases need the high-speed train to barrel through.

But slowing a case down is often the only way to stop it from being decided before it’s understood. Because these days, the space to exercise judgment without being punished for it has narrowed. And when that space disappears, so does the kind of lawyering people still think they’re seeing.

Those conditions used to be easier. They were imperfect but still available. Now they’re treated as inefficiencies.

Having learned this, when praise arrives, it doesn’t land as affirmation. It lands as a reminder of a mismatch: between what people think they’re seeing and what the system actually permits. Between a cultural memory of law work as it once was and the reality of practicing it now.

That gap creates a particular kind of unease. Not because the praise is undeserved — though I’ll admit that’s usually how I feel — but because it points to something that no longer fits cleanly inside the machinery of modern criminal courts.

Once that misalignment becomes visible, it’s hard to ignore — especially for those still trying to do the work from inside the system. From conversations with colleagues, I know I’m not the only one seeing this.

What Changed

The law didn’t change in any fundamental way. The Constitution didn’t change. The formal rules governing criminal cases are largely the same ones I was working under years ago.

What changed was how cases move.

Over time, calendars tightened and dockets swelled. Speed became a virtue in its own right, especially for judges, prosecutors, and the money-grubbing type of defense “attorney”. Time stopped being something to use and started being something to measure efficiency. The system adapted to volume brought on by overcharging, over-legislating, and dehumanization. And in doing so, it learned how to function without stopping very often.

That shift had consequences. Practices that once felt ordinary — taking time to investigate, filing motions that slowed a case down, insisting on hearings that required real attention, making sure clients and their families understood things — began to feel disruptive. Judgment became harder to exercise without cost. Delay, even when purposeful, started to look like obstruction.

The values didn’t disappear. They’re still invoked regularly. But the system increasingly operates in ways that make honoring them difficult, and sometimes actively unwelcome.

I’ve made this same argument in more formal terms elsewhere. In a Daily Journal article published January 6, my friend and colleague and I wrote about pretrial detention and constitutional compliance — about how the law itself hasn’t meaningfully changed, but courtroom practice has. About how speed, scale, and administrative convenience have gradually replaced individualized judgment.

That piece was written for lawyers and judges. This one is written from inside the same problem.

That’s the environment in which praise now lands oddly. Not because the ideals are unclear, but because the machinery has learned how to move without waiting for them.

Mourning Has Broken

For a long time, I resisted the language of mourning.

Mourning suggests finality. It suggests acceptance. And acceptance is not something I’ve been willing to grant a system that continues to insist that it still stands for the same values it always has.

But at some point, the word stopped feeling optional.

When a system no longer allows the work it claims to honor, something breaks. Not all at once. It doesn’t collapse in one dramatic moment. Like the stocks I love to complain over, it’s been a slow downward churn. Things broke quietly, through repetition. Through small concessions that, to those who couldn’t spot the pattern, didn’t look like concessions at the time. Through practices that used to be ordinary and now feel oppositional.

What broke here isn’t commitment. Or effort. It’s the assumption that the work will be met halfway.

That’s the break of mourning, of mourning what’s broken.

Long before I became a lawyer, I wrote a poem built around a phrase I had stumbled across almost by accident: “the payment of a debt which cancels all others.” I shouldn’t have understood this, because I was only 16 years old. Hell, I’d never even had a real girlfriend yet when I wrote this. But there was a strange clarity for me in those words, revealing a pattern I’d already come to recognize.

As I just alluded to, that poem was written decades ago. I’ve written more about the poem here, but I want to quote it in this article because I think it has a new meaning for me that fits this context. It reads like this:

Testimony to the Payment of a Debt

As I sit gazing out the window,

The stars slip silently past.

And the edge of the moon,

Sticks out from behind the mountains,

On an ever-increasing downward plunge…

This is the beginning of an empty day.Last night I sat here,

Thinking of all the times,

You and I once shared;

Wondering over and over,

What it was that came between us,

When all along I knew it was me.Looking up now into the birth of the sky,

The mountains begin to glow,

And the sun peels off its blankets;

Melting the black coverlet of space,

Leaving me naked and alone,

To face a day without you.“I want her back in my life!”

My mouth forms the words,

But the sounds are absorbed,

By a vast and uncaring world.

“I want her back!” I cry;

Yet no one hears, save me.And now the unbidden rays of sunlight,

Invade the once Stygian darkness of the room,

Illuminating the medicine bottle on the table;

The vacuousness of which,

Is testimony to the payment…

Of a debt which cancels all others.

You see, at the time, I thought I was writing about personal loss. I didn’t yet have the language to understand what I was really circling: the moment when something is over, not because you chose to end it, but because continuing to pretend otherwise would be dishonest.

More recently, the language returned — differently. Shorter. Sharper. Less patient. A new poem popped into my head when two people in one day referred to me as being like the Lincoln Lawyer. This is the poem as it came to me, unfiltered:

Mourning Has Broken

Mourning has broken

like the first mourning.Injustice has spoken…

Like the Last Judge.Praise for the Lincoln,

Lincoln the Law-a-a-a-yer.Time to retire,

Get my butt out.

These are not the same poem, and they’re not saying the same thing.

The first registers loss after the fact. While the second registers recognition in real time. I guess I’m learning chart-reading after all.

But the poems…together, they mark the distance between endurance and acknowledgment — between continuing to work and admitting what that work has become inside a system that no longer meets it halfway.

Mourning, in this sense, isn’t retreat. And it isn’t resignation. It’s simply the result of recognition.

And once that recognition sets in, it changes how everything else is heard — including praise.

Back to the Lincoln Lawyer

So when these folks suggested I was like the Lincoln Lawyer, I got it. (At least, I think I did! Tell me in the comments if I’m wrong!)

People are reaching for a figure who represents attentiveness in a system that often lacks it. Someone who doesn’t rush past people. Someone who stays present when things get uncomfortable. Someone who knows when not to move yet.

That image still resonates because it describes a kind of lawyering people wish the system still made room for.

But here’s the part that makes the praise land oddly: Mickey Haller works in a world where slowing things down is still legible as skill. Where calling for time isn’t treated as resistance. Where judgment can still interrupt momentum without being punished for it.

That’s not the world most criminal defense lawyers are practicing in now.

Today, restraint is often misread as weakness. Delay is treated as obstruction. And the pressure to move — always to move — overrides the quieter work of understanding what’s actually happening before irreversible decisions get made.

In markets, when things move too fast, trading is halted. Everyone understands why. Truth can’t be discovered at that speed.

Criminal courts don’t have that safeguard. So the burden falls on lawyers to call for time anyway — to ask the system to pause when it would rather barrel ahead. To stop participating in conveyor-belt justice.

That’s not cinematic. It doesn’t look heroic. And it rarely gets recognized for what it is.

So when the Lincoln Lawyer shows up in conversation now, I hear something else underneath the compliment. I hear a recognition that the kind of lawyering people still admire is becoming harder to practice — not because lawyers forgot how to do it, but because the system learned how to move without allowing for it.

Which brings me back to where this started.

I don’t fully get the comparison. I don’t think I fully understand how it applies to me — or maybe I just missed what those who said it intend. But to the extent I can accept any part of it, it’s probably because, at least for now, I still feel a kind of obligation to be a problem.

Not in the sense of being oppositional for its own sake, and not because I think the past was some golden age we can simply return to. But because so much of what now passes for efficiency in criminal courts depends on things moving too quickly to be questioned, and because slowing that movement down has become one of the few remaining ways to insist that evaluation, consideration — real judgment, not judgmentalism — still matters.

That’s what I mean when I talk about dragging a case. It’s not a piece of nostalgia. It isn’t theater. What it is is an attempt to keep cases from being decided before they’re actually understood, even when the system would very much prefer not to wait: “Who stopped the conveyor belt?”

Doing that now often feels less like practicing law and more like throwing a wrench into machinery that has learned how to run without stopping.

So when the Lincoln Lawyer showed up yesterday — first from a client, then from a friend — I heard something underneath what I took as a compliment. I hear a recognition of a kind of lawyering people still want to believe exists, even as the conditions that once made it ordinary continue to disappear.

These vanishing conditions don’t mean the work is over — like I argued in the Daily Journal, it’s a reason defense attorneys need to revive some old tools. (There, I spoke of the need for more habeas litigation.)

What it does mean is that praise, by itself, no longer tells the whole story. In this context, it’s less an affirmation than a signal — an echo of values we still know how to name, even as the system grows increasingly impatient with the people who insist on embracing them anyway.

Rick, you do the right thing even when it is the hardest thing to do.

I’ll explain what I personally think it meant. You have conviction and you stand by it. Your clients are better off for it.