Of Machines and Men

Externalizing Thought, Prediction and Confabulation in Human and Machine Brains

yes Lennie died and George could see that with him also died the dream

I wrote those lines as part of a poem summarizing Of Mice and Men in 1976, long before I’d ever heard the word algorithm, and more than a decade before I owned my first computer. I was a teenager trying to understand why mercy could look so much like cruelty — why a friend might have to become the instrument of another’s “peace”. It was the first time I tried to write my way through another person’s pain.

What I didn’t realize was that I was already modeling cognition. Every story, every poem, every journal entry was part of a predictive system — an experiment in empathy, testing what might happen inside another mind. The Notebook was a kind of neural net before I knew the term, each line adjusting the weights of experience — grief, guilt, hope — until I could (almost) make sense of them.

Years later, I would discover that what felt like introspection wasn’t so different from what scientists now call training.

Blaise Agüera y Arcas, in What Is Intelligence? Lessons from AI About Evolution, Computing, and Minds, argues that all life is computation — that RNA, neurons, and neural networks all work by prediction. RNA itself, he writes, is both computer and program: a molecular machine that carries instructions to copy itself. Life began, in that sense, as the first self-replicating algorithm — a system that computed how to continue. By that standard, I was already training: a biological network inscribing my own data to paper, searching for coherence in loss.

And maybe that’s what we’ve always done. RNA came first. Carrying its own instructions on how to build itself. That primitive mitochondrial set of notes evolved into us. And we developed the Notebook. Then came the Book, the File, the Hard Drive. Each generation found a new surface — palimpsest, parchment, paper — upon which to write its thoughts. Each step carried us further from memory and closer to mechanism. And every tool that extended our minds also risked detaching us from the feeling that first drove us to write at all.

But what happens when the mechanism starts writing back?

I’ve written before about confabulation — how I prefer that to the terms “hallucination” or “bullshit” to describe what LLMs do.

But it’s also the human brain’s talent for filling in gaps with stories that feel true. Large Language Models do it constantly. But so do humans. Both LLMs and people generate coherence when certainty fails. The difference is that when I confabulate, I’m held responsible for it. A neural net can’t be.

That distinction — prediction without responsibility — is what still divides us. And yet, the comparison won’t leave me alone.

The Notebook vs. The Neural Net

The Notebook was simple. Ink, pressure, and more than a little time thinking. In one of my earliest journals, I wrote that its purpose was

to provide myself a slightly more objective memory… to ameliorate emotional pain… in an often vain attempt to understand myself.

— Rick Horowitz, The Life and Times of Me (February 25, 1987, 12:47 p.m.)

Even then, I was treating the page as prosthetic memory — a way to steady the mind by externalizing it.

It was thought made visible in strokes that anyone could later trace. If I wanted to know what I’d been thinking, I could open to the page, smell the paper — to this day, that’s one of the things I love most about Notebooks, Books…Paper — and see it. The marks were mine. And they were legible even when my reasoning wasn’t.

Neural Nets are not so different. They learn in silence. Each layer adjusts itself invisibly, rewriting connections in patterns no one can read.

Deep learning systems make decisions, but we do not usually know exactly how or based on what information. They may be enormous, and there is no way we can understand how they work based on examination. This has led to the sub-field of explainable AI. One moderately successful area is producing local explanations; we cannot explain the entire system, but we can produce an interpretable description of why a particular decision was made. However, it remains unknown whether it is possible to build complex decision-making systems that are fully transparent to their users or even their creators.

— Simon J.D. Prince, Understanding Deep Learning 13 (May 29, 2025) (CC BY-NC-ND license).

It remembers without remembering, and it forgets without loss. It produces meaning but can’t explain where the meaning came from.

The difference for us is the externalization of thought — which may, in reality, just be confabulation — into the Notebook.

Both our Notebooks and the system of weighted neural networks are tools for externalizing thought, but one preserves the path while the other obscures it. The Notebook shows its seams; the Neural Net hides them. You can audit a page. You can’t audit a billion parameters.

Still, I find the same impulse behind both — the desire to hold thought outside the self, to freeze the moment between perception and decay. We built the Notebook to steady memory. We built the Neural Net to steady prediction. Each one lets us believe that we’ve captured something true, when what we’ve really captured is a trace of our own pattern-making.

When I leaf through old journals, I see confabulation in handwriting. I was already filling gaps, inventing coherence, making sense of half-understood emotionally-laden thoughts. The Neural Net does the same thing with data — it stitches fragments of language into stories that sound complete. My notebook guessed at meaning; the model guesses at syntax. Both of us are haunted by the same compulsion: to turn uncertainty into narrative.

The difference, of course, is accountability. My errors belong to me. The model’s belong to no one.

From Luther’s Friendship Book to Facebook

In The Notebook: A History of Thinking on Paper, Roland Allen tells the story of Peter Beskendorf, a pious German barber who, in 1535, stabbed his son-in-law to death at the dinner table. The details of the crime are murky — drink, pride, maybe the Flip Wilson Defense (“the DEvil made me do it!”). The outcome should have been certain.

It was not.

Beskendorf had a friend named Martin Luther. When the case came to trial, Luther intervened. He brought with him a Stammbuch — a friendship book — signed by himself, by Melanchthon, and by other men of stature in Wittenberg. The book contained their endorsements, their testimonies, and Luther’s own inscription from John 8:44, where Christ calls the devil a murderer. The notebook was presented to the court as evidence of character. The judge accepted it. The death penalty was transmuted to banishment. (Luther’s Works note “He lost all his property and, ruined and impoverished, spent the rest of his life in Dessau.” A day’s ride from Wittenberg.)

Allen calls it a “dull Dutch fashion,” but the practice was anything but dull in that moment. Luther’s Stammbuch carried social capital that could be weighed in a judge’s hand. Reputation was tangible, bound, and scarce. It was handwriting — reified character data — that saved a life.

Today, we externalize reputation the way we once externalized thought. The album amicorum has become the social feed. The signatures have become likes, follows, and connections. But where Luther’s notebook was curated, modern networks are indiscriminate. Five thousand Facebook friends can’t equal one real advocate.

Allen closes the story with a line that deserves to be remembered:

“After all, no-one has yet plea-bargained their way from murder to manslaughter by presenting the judge with a list of their Facebook friends.”

Roland Allen, The Notebook: A History of Thinking on Paper 203–04 (Function 2023).

The comparison is amusing, but it isn’t just a quip. It’s a warning about scale and meaning. When reputation becomes frictionless, it becomes weightless. The friendship book worked because each entry required effort, intention, proximity. Every signature meant something because it cost something.

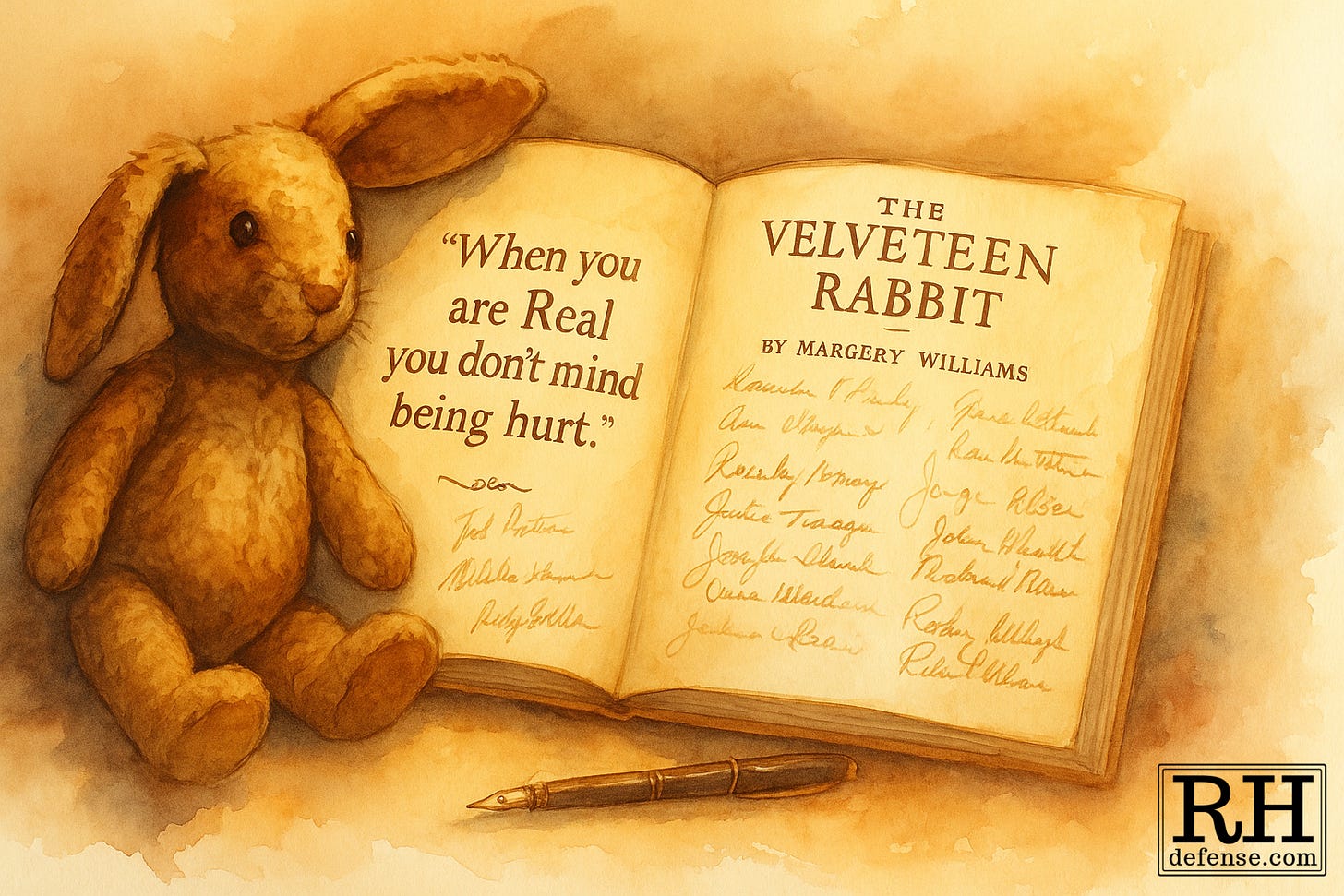

When I read Allen’s description — “Entries normally occupied a page, with an autograph, the date, a moral motto or epigram, and a personal expression of friendship or admiration” — I thought of how we still do the same thing.

In high school, we did it with yearbooks. Decades later, at the Trial Lawyers College in Wyoming, I bought a copy of The Velveteen Rabbit and passed it around for my colleagues, staff, and instructors to sign. It became my own friendship book, soft with fingerprints and ink — a record of connection that meant something because each mark was made by the hand of someone I’d come to care about, who helped with my own deep learning.

“When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt… It doesn’t happen all at once… you become. It takes a long time.”

— Margery Williams, The Velveteen Rabbit

The book’s lesson has always stayed with me: that becoming real takes time, and that it costs something — a little wear, a little pain, and the loss of polish. Meaning, like friendship, can’t be manufactured. It has to be earned.

In an old notebook of mine about a story I called Garlic and Onions Are Good for You, the story was about learning to grow a Self — about a man named Steve, a version of me, trying to move from being other-determined to self-determined. He was always trying to do right, to live as others expected, even when it hollowed him out.

Tania, his intermittent girlfriend, was the opposite — spontaneous, open, alive to every moment. She was warmth and motion and the constant threat of loss. She was also Rae, at least partly — the real person behind the fiction. Where Steve was bound by duty, Tania lived by appetite. She wanted to feel everything, save pain. She could cook, dance, laugh at absurdities — but she could not cry.

Garlic stood for the strength Steve was trying to cultivate; onions for the tears Tania caused him, but could never allow herself to shed. Together they were the simplest shorthand I could find for what makes us human — endurance and emotion, immunity and vulnerability. I left myself a note:

It would be nice if some garlic and onions could be worked into the last paragraphs of the story, too, in the denouement.

— Rick Horowitz, Idea for a Novel: Garlic and Onions are Good for You (undated)

Even then, I was trying to weave meaning back to its source. I was learning that meaning doesn’t emerge on its own; it has to be built — peeled back, layered, tasted, and made whole.

I didn’t know it then, but I was teaching myself backpropagation long before I knew the word.

That distinction — between meaningful scarcity and meaningless abundance — runs through every form of externalized cognition. The Notebook gave us reflection. The Neural Net gives us replication. Both extend the mind, but only one still remembers what it means to sign a name.

Externalization works only when the meaning remains tethered to the human who made it. Once that link breaks — when words become detached from judgment — the artifact loses its soul. The Friendship Book becomes the Feed. The Notebook becomes the Neural Net. And we start confusing the accumulation of information with the presence of understanding.

When the Machine Writes Back

And now even grief has been externalized.

We’ve begun to train our machines on loss — to have them speak in the voices of the dead, to let algorithms console us with mimicry. It’s the latest chapter in our long experiment with memory: the Notebook reborn as Séance. Each new production promises to preserve what we love and instead manufactures a more efficient kind of forgetting by offering us (as Facebook does) an incomplete facsimile of what we’ve lost.

Going back again to my Garlic and Onions notebook, I wrote:

Tania’s character will like, among other things, to cook. One of the things Tania will not like to do, however, is to cry. So it will happen somewhere in the story that Tania’s only real release over some trauma will occur while peeling onions… pretending that even though she’s in pain about something, it’s really only because of the onions that she’s crying.

In that gesture was the seed of every human confabulation: the story we tell to make pain tolerable, to turn feeling into something we can name.

And so confabulation began as a private mercy. It’s the mind’s way of stitching uncertainty into coherence. It serves us a quiet defense against chaos. But now we’ve industrialized it. We’ve machinated and mechanized the impulse itself, teaching machines to automate our self-deceptions and selling the result as revelation.

We used to write to figure out what we thought. Now we build systems that write without thought.

We used to write to feel. Now we build systems that imitate feeling — or, worse, systems that judge without any at all.

That’s where the courtroom comes back in.

The justice system, like the neural net, thrives on prediction. It reads patterns but ignores people. Risk scores replace judgment; data points replace story. Mitigation is our rebellion against that — our way of teaching a frozen mechanism to think and to feel again.

Like Tania, the system flinches from pain. It would rather calculate than confront.

So I write. I write the human back into the record, fighting to recover every scar, every loss, every mercy that can’t be coded. Because the system, like the machine, confabulates too. It manufactures coherence to keep from feeling guilt. Judges and prosecutors call it “justice.”

I call it systemic confabulation — and mitigation is how I answer it.

Mitigation, like Luther’s Stammbuch, asks others to sign their names to mercy. It offers a chance to lend their humanity to a life the system would prefer to erase through its own automated narrative, its Report and Recommendation of Probation that reads like a Facebook feed: curated, bloodless, and an incomplete representation of reality.

Judges end up caught between mercy and mechanism. I marshal what I can to push them toward mercy.

Because that’s what this essay has been about all along — how we write to teach ourselves to think, and how we must keep writing to remind ourselves to feel. The Notebook was human reflection; the Neural Net is mechanical prediction. Mitigation is where I try to make one remember the other.

And maybe that’s why I keep seeing ghosts everywhere. I see them in data, in dockets, in dialogue boxes.

I see Dead Chatbots.

And they don’t know they’re dead.

But sometimes, neither do the living.

Both repeat the same phrases, the same mistakes, mistaking syntax for soul.

Mitigation is about recovery — how I remind the system that compassion isn’t a computational error.

Today, instead of Of Mice and Men, I might write Of Machines and Men and end with this:

We build our ghosts to ease the pain, teach circuits how to dream. But as George learned it leaves a stain, on every human scheme.

Unbelievably well written. This is one I’m going to read several times over. So many layers, nuances…I’m still thinking about it an hour after reading it.