Cornering Power

Why Power Cannot Be Monopolized Without Breaking the System

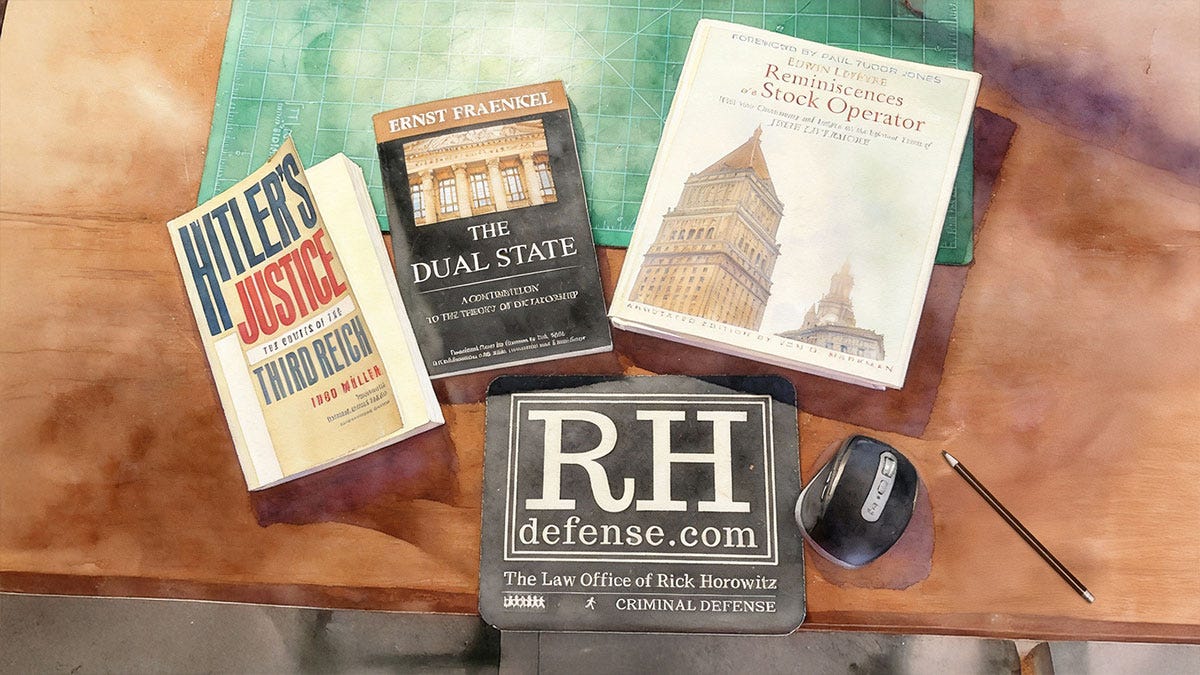

Interesting things happen in my ADHD brain when I pay attention to multiple things at once. Right now, for example, I’m reading Reminiscences of a Stock Operator — Edwin Lefèvre’s account of the life and times of Jesse Livermore — while watching what is happening in Minnesota, what has already happened to Congress and the courts as they are sidelined, and the growing illegitimate powers being exercised by one man.

Full disclosure: I normally try to write my posts so that they connect in some way with criminal defense, since I am a criminal defense lawyer. I’ve done this even when writing about AI, or using stock market metaphors. This one will be a little more general. It’s still about law — specifically the importance of the Rule of Law to our institutions and the form of government we’ve generally adhered to up to now.

Cornering Markets

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, men like Vanderbilt, Gould, Fisk, Drew, and others believed they had discovered a simple truth: if you could corner a market, you could control reality.

Control supply, starve liquidity, force everyone else to come to you — and the price would be whatever you said it was. But price wasn’t always the point. Often, it was vanity. They wanted the power to make other men bow to their will.

Sometimes it worked. Briefly.

Occasionally it worked longer than anyone expected.

But every attempt to corner a market extracted a cost. Counterparties defected. Credit thinned. Governments intervened. Even when the corner held, the system that made it possible did not survive intact. Markets didn’t always collapse — but they were distorted, hardened, and reshaped in ways that outlived the men who thought they were in control. In the process, it sometimes destroyed the fortunes of all parties involved. Some never recovered. They died of heart attacks. They died by their own hands. They died destitute and shamed.

Today, we are watching an attempt to corner something far more dangerous than railroads, wheat, corn, or copper.

Power cannot be monopolized without breaking the system that once gave it legitimacy, flexibility, and reach.

We are watching an attempt to corner power itself.

Whether this follows the familiar pattern of past corners, or marks something genuinely new — unprecedented in more than two-and-a-half centuries of American history — remains an open question. What is not in doubt is this: power cannot be monopolized without breaking the system that once gave it legitimacy, flexibility, and reach.

The Logic of a Corner

A market corner is not simply an attempt to dominate supply. It is an attempt to eliminate any exit — to make it impossible for others to walk away without paying whatever price the cornerer demands.

The cornerer’s theory is straightforward: if every meaningful pathway runs through the cornerer, then price becomes irrelevant. Value is no longer discovered through ordinary market processes — through buyers and sellers negotiating freely — but is dictated. The market stops being a forum for exchange and becomes a site of compulsion. Participation is no longer voluntary. It is mandatory.

But that theory depends on a fragile assumption — that everyone else must continue to play by the old rules even after the rules have been broken.

In practice, corners succeed only so long as three conditions hold. First, liquidity must remain constrained — meaning there must be no easy way for participants to move their money, their goods, or their commitments elsewhere. Second, counterparties must lack viable alternatives. Third, enforcement — whether legal, political, or financial — must remain credible. Once any of these fail, the corner begins to unravel, sometimes quietly, sometimes violently.

What makes corners dangerous is not that they always collapse. It is that even when they hold, they deform the system that sustains them. Credit and even cash become scarce or punitive. Participation narrows. Innovation slows. Trust evaporates. The system becomes brittle, dependent on constant pressure to maintain the illusion of control.

Political power operates under a similar logic. It is not owned; it is extended. It depends on compliance, belief, and habit. Courts function because their judgments are treated as binding. Legislatures function because their allocations are honored. Agencies function because rules are enforced consistently rather than selectively. None of this is self-executing.

To corner power, then, is to do more than seize authority. It is to sever alternatives. To remove the possibility of institutional exit — the ability of courts, states, agencies, or individuals to say no and still function. It is to make compliance the only viable option, not because it is legitimate, but because resistance has been rendered too costly or too dangerous.

At first, this can look like strength. Decisions happen quickly. Opposition quiets. Outcomes become predictable. But predictability achieved through compulsion is not stability. It is leverage masquerading as order.

The longer a power corner holds, the more resources it consumes merely to sustain itself. Enforcement expands. Exceptions multiply. Emergency measures become routine. What once required consent now requires pressure. What once relied on legitimacy now relies on fear, loyalty tests, or exhaustion.

This is the paradox at the heart of every corner: control increases even as capacity shrinks. The system continues to function, but at a higher cost and with less resilience. It can persist this way for years — sometimes for decades. But it no longer adapts. It no longer corrects. Problems are not resolved, only deferred.

And when a system stops resolving problems, the damage does not announce itself all at once. It accumulates — quietly, structurally, and often irreversibly.

Law as Liquidity

In functioning systems, law plays the role that liquidity plays in markets.

Liquidity is what allows participants to move — to enter, to exit, to adjust positions without catastrophic loss. It doesn’t eliminate risk. It makes risk survivable.

When I first started learning day trading, once or twice — that’s all it took to teach me — I bought stocks just because they were going up. Sometimes fast. And then I tried to sell when I thought it time to take my profit. To get out before the climb ended.

But I had bought into a stock with low liquidity. I got trapped. Fortunately, I had at least enough smarts to know that as a beginner, I should trade small. I didn’t like the losses, but they didn’t destroy my account.

In markets, liquidity lets you in or out more easily. Prices change without freezing the system. In institutions, law works similarly. It lets society function and power change hands without violence.

Courts provide this kind of liquidity. So do legislatures. So do agencies operating under stable rules. They create predictable pathways for disagreement, correction, and redress. They allow conflicts to be resolved rather than escalated. They let losing parties remain participants rather than becoming enemies.

Americans haven’t always liked this and some have turned quite cynical (and I might say “inappropriately cynical”) when they see it: Bush and Obama got along because our system worked to the benefit of all; not because “they’re all the same”. That’s why I’ve always resisted that argument.

But this particular “law liquidity system” only works if outcomes are honored.

A court order that is ignored does not merely fail to constrain the executive. It signals to everyone else that the exit ramp no longer functions.

This pattern is not new. As Ingo Müller documents in Hitler’s Justice (Amazon Affiliate link), authoritarian systems rarely abolish courts or legal procedure. Judges remain. Hearings continue. Opinions are issued. What changes is not the form of legality, but its function. Law no longer restrains power; it is used to rationalize it.

Müller’s point was not that courts vanished, but that their continued operation made the transformation harder to see — and easier to accept.

[A] dictatorship which clothes itself with a tinsel of legal form can so far depart from the morality of order, from the inner morality of law itself, that it ceases to be a legal system. When a system calling itself law is predicated upon a general disregard by judges of the terms of the laws they purport to enforce, when this system habitually cures its legal irregularities, even the grossest, by retroactive statutes, when it has only to resort to forays of terror in the streets, which no one dares challenge, in order to escape even those scant restraints imposed by the pretence of legality—when all these things have become true of a dictatorship, it is not hard for me, at least, to deny to it the name of law.

— Lon L. Fuller, Positivism and Fidelity to Law — A Reply to Professor Hart, 71 Harv. L. Rev. 630, 660–61 (1958)

Ernst Fraenkel (Amazon Affiliate link) described this kind of system as a “dual state” — one in which a normative legal order continues to exist on paper, while a separate prerogative system operates alongside it, unconstrained by law and justified by necessity.

Similarly, a legislative appropriation that is selectively withheld tells institutions and individuals alike that compliance is no longer reciprocal. The rules still exist on paper, but the system has lost its ability to legislate outcomes.

This is why, as a criminal defense lawyer, I have sometimes been critical even of the courts and judges. The Supreme Court, rather than adhering to precedent, says it’s okay for ICE to racially profile or for our current President to do what no other executive has ever done — or would ever have been allowed to do. At the local level, Superior Court judges hand out pretrial release orders like conservative candy, ignoring more than two centuries of law to the contrary, as I and my colleague have written in The Daily Journal. Even if I could, though — and, yes, I know that I can’t — I would not ignore the courts.

Because when legal liquidity dries up, power does not disappear. It pools.

Decisions become centralized not because the system fails to distribute authority, but because distributing authority is precisely what a successful corner on power eliminates. When legal and institutional exits are blocked, power pools by design. Discretion replaces rules. Exceptions replace standards. Outcomes depend less on process than on proximity to power — because once the corner holds, access replaces law as the organizing principle.

This can persist for a long time. Systems don’t collapse simply because law is ignored. They adapt — but in ways that favor those already positioned to absorb risk. Smaller actors lose access first. States, agencies, and individuals with fewer resources find that resistance carries disproportionate costs. Over time, compliance becomes less about legality than about survival.

What makes this phase especially dangerous is that it often feels orderly. There are fewer visible disputes. Fewer open conflicts. Decisions appear decisive. But this quiet is not stability. It is the absence of safe disagreement. (Not to mention of due process.)

In markets, the loss of liquidity does not announce itself with a bell. Instead, trading slows. Spreads — the distance between what a buyer is offering and a seller asks — widen. Volatility clusters. Then, one day, something that should have been manageable becomes catastrophic because there is no longer a way out.

Institutional systems behave the same way. When law ceases to function as liquidity, problems do not vanish. They stack. They compound.

When institutional failure becomes visible — when courts issue orders that are ignored, when legislatures allocate funds that are never released, when rules appear optional rather than binding — conflict does not remain abstract.

It surfaces. Often first as protest. Often peaceful at the outset. But protests are not the cause of institutional breakdown; they are a symptom of it. And when people no longer believe that lawful channels will respond, restraint becomes harder to sustain.

When the law breaks, the safeguards all fall, And down comes the Republic, freedoms and all. — Rick Horowitz, When the Law Breaks: The Rule of Law Will Fall & Down Comes Our Republic (April 6, 2025)

The Cost of a Successful Corner

The most dangerous misconception about corners — whether in markets or in power — is that they must succeed in order to matter.

They don’t.

All attempts at cornering have impact at least for a time. Some last long enough to reshape incentives, institutions, and expectations. By the time they loosen, the system they once operated within has already been transformed. The damage is not measured by collapse, but by what no longer functions the way it once did.

Markets taught us this long ago. A successful corner doesn’t need to bankrupt everyone involved to be destructive. It only needs to distort behavior long enough that trust erodes, risk concentrates, and ordinary participants are priced out of meaningful choice. Even when prices eventually normalize, the market that returns is not the market that existed before.

Power works the same way.

A political system does not need to fall apart to be broken. It only needs to stop resolving conflict fairly, predictably, and reciprocally. Once that happens, legitimacy becomes optional. Compliance becomes strategic. Survival replaces consent as the organizing principle.

What remains may still look like a functioning system. Courts still sit. Legislatures still meet. Elections may even still occur even if they no longer count at all — think “stock manipulation”, which, after all, is part of cornering. But the logic has changed. Outcomes matter more than process. Loyalty matters more than law. And power, once centralized, becomes easier to inherit than to challenge.

Markets eventually record this damage in prices, liquidity, and volatility. Political systems record it in distrust, polarization, and periodic eruptions of unrest. The bill always comes due, but not always to the person who first ran up the tab.

That is the lesson markets offer — and the warning they carry.

Power can be cornered for a time. It can even be held for a time. But it cannot be monopolized without breaking the system that once gave it meaning. And when that system breaks, it does not vanish. It persists — altered, hardened, and less capable of correcting itself than before.

Whether that is where we are headed, or whether we step back before the damage becomes permanent, remains unresolved.

What is already clear is that corners do not end cleanly.

They end by changing what survives them — in this case into something that no longer even remotely resembles what was originally constituted.