The Curse of Expertise and the Craft of Defense

How a miswired network, my father’s Navy story, and a stubborn judge all taught me the same lesson about curiosity and control.

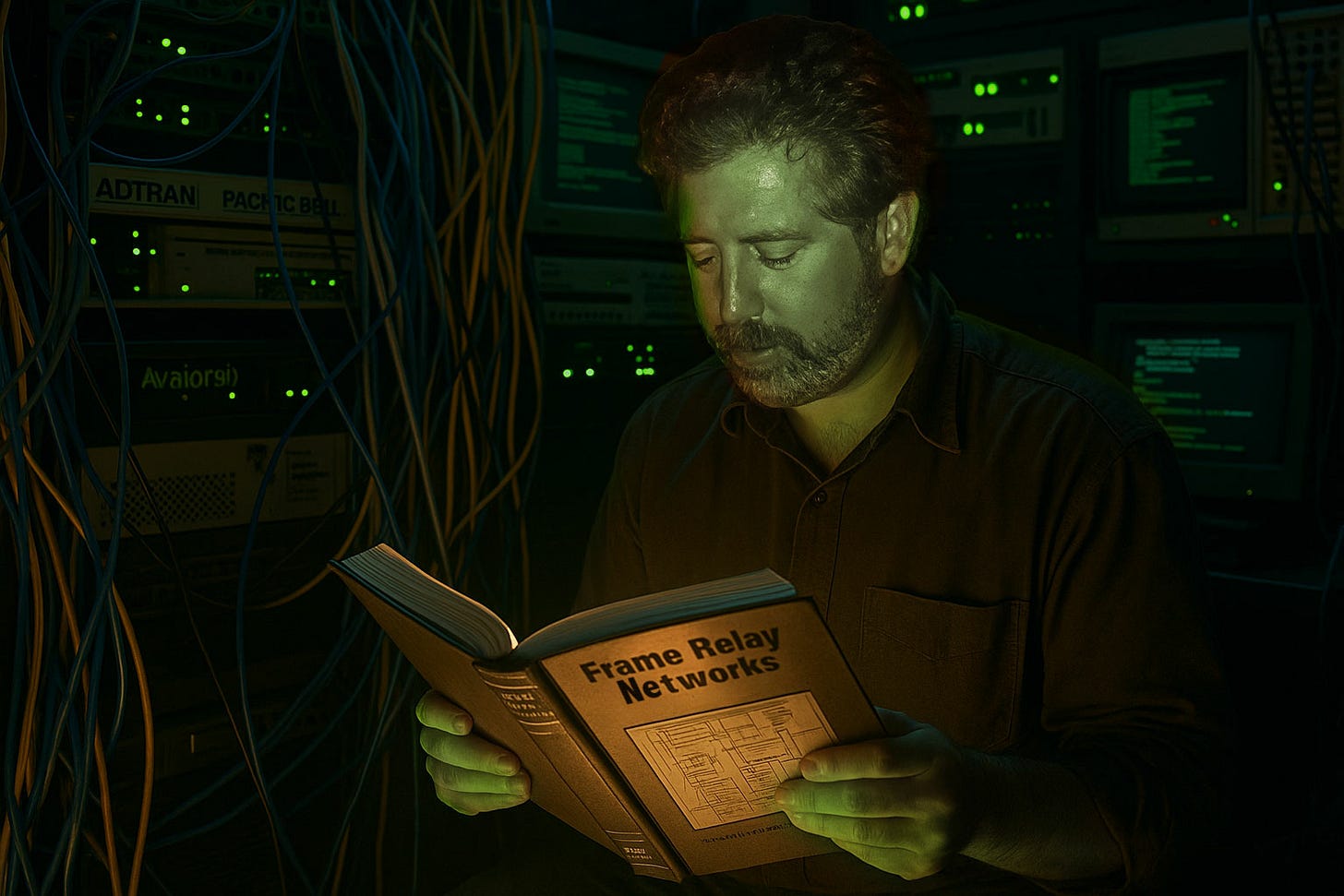

In Over My Head

I was in over my head, and I knew it.

Back then I was working at ValleyNet — having started before it became Protosource — and we were trying to bring high-speed internet to people in the days when “high-speed” meant something faster than 56k modems yet unfortunately still slower than a T1 line (quite expensive). We had already expanded into several other cities throughout the Central San Joaquin Valley and needed a faster way to connect people connecting to those outlying hubs back to the main server in Fresno.

The new-fangled (to us, anyway) “Frame Relay” service wasn’t working the way it should. I spoke to each of the vendor’s whose equipment we used to tie everything together. Adtran said the problem was Pacific Bell’s. Pacific Bell said it was Adtran’s gear. Cisco said their set-up was fine. Everyone was right, apparently, and no one was responsible.

Ultimately, it was my problem to solve and I didn’t know enough to solve it. So I did what I still do when I’m in over my head: I read. I found a book by Uyless D. Black called Frame Relay Networks: Specifications and Implementations and tried to make sense of it over one long weekend. By Monday morning, I understood just enough to be dangerous.

I started by calling each company again, asking things like, “If I understand what you’re saying, then why would ___ happen?” or “Can you explain this part to me one more time?” The answers didn’t line up. So I decided the only way to get a straight story was to get everyone on the same call where they couldn’t point fingers at people who weren’t there.

I knew enough to know that I was getting nowhere the way things were. I’d learned enough over the weekend to realize that some of what I was hearing didn’t make sense. Now, I was by no means an expert, mind you. I barely understood what I had read. But I guess I got enough to ask questions that made the experts pay attention.

Or maybe it was because I had the ability to pay, or not pay, for their services. (I suppose it’s also possible they cared enough to try to fix things once we’d gotten past the finger-pointing and started working together!)

When I finally said, “What if we tried this?” I wasn’t making a grand technical proposal. I was guessing. Still struggling to connect the dots between what I’d read and what I’d heard. But the line went quiet for a second. Then one of them said, “That might actually work.”

And it did.

I wish I could say I knew what I was doing, but I didn’t. I’d stumbled into the solution because I didn’t know enough to rule anything out. The people on that call knew more than I ever would — but they also knew too much. Their knowledge had hardened into certainty, and certainty is a terrible problem-solver.

Solving that network wasn’t about brilliance. It was about refusing to promise what I couldn’t deliver and doing the next right thing until the system made sense.

I don’t make empty promises, because I only make one promise: That I will use all my training, my knowledge, and my skill to fight the best fight, for the best result, that I can. That is the one promise that I can always keep.

And the best way I’ve found to do that is to take things one step at a time.

— Rick Horowitz, The One-Step-At-A-Time Guy: Lawyering into the Dark (October 31, 2021)

The Curse of Expertise

That day taught me something I didn’t have a name for yet: the curse of expertise. The more fluent people become in a system, the more they stop hearing their own assumptions. They talk to one another in closed loops, answering questions no one outside the loop would ever think to ask — and missing the obvious ones a beginner can still see.

That’s where the “one-step-at-a-time” discipline earns its keep. If expertise can blind you, steps keep you honest.

It’s a pattern I’ve run into again and again since then and not just in technology, but in courtrooms. In retrospect, I realize I’d seen it before I ever set foot in either world.

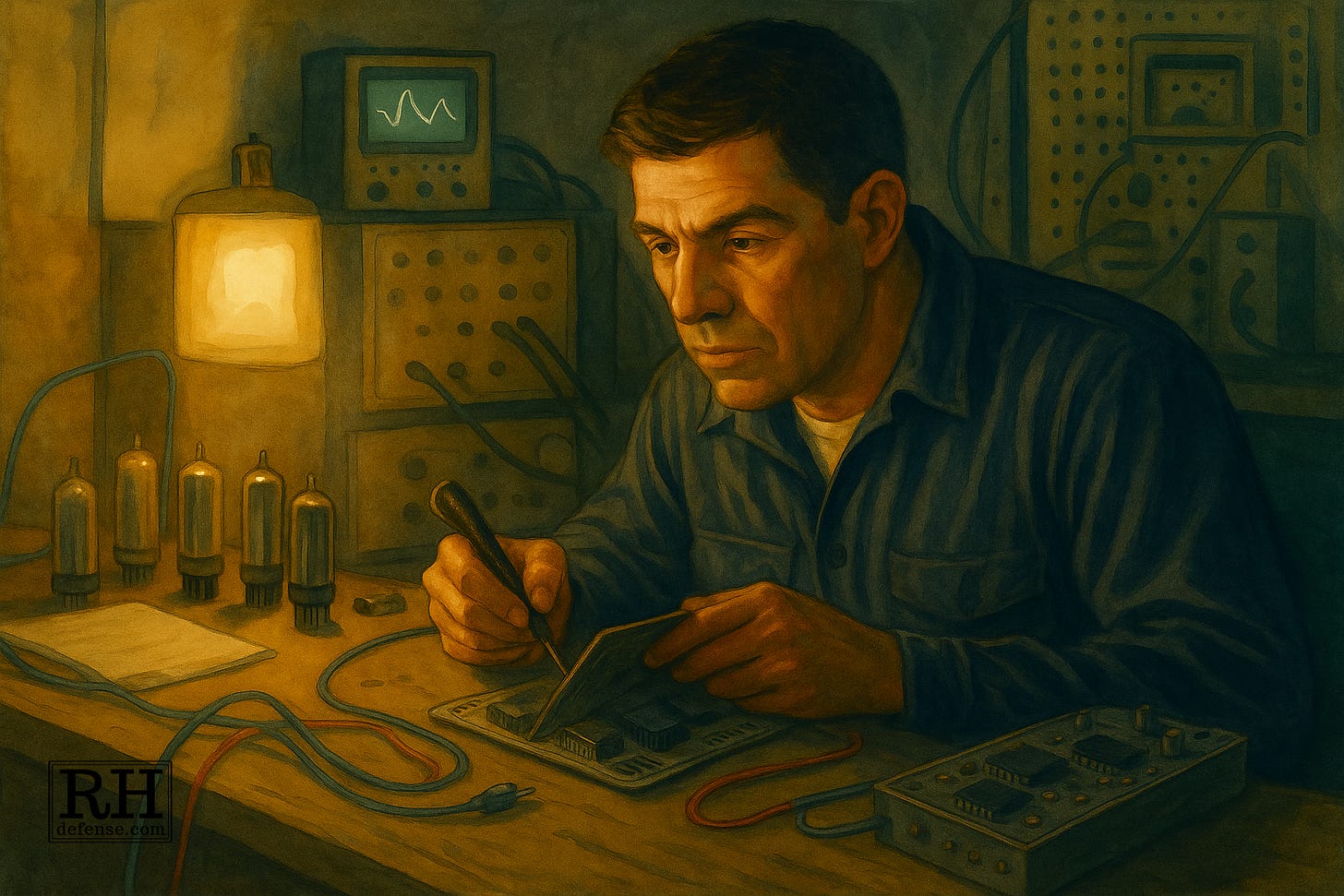

The story seems almost unbelievable. Almost a joke. But my father lived it.

He told me the story of how, in 1958, he joined the Navy, wanting to become an aircraft mechanic.

The Wrong Line

During Navy boot camp, he stood in the wrong line when it came time to choose which school he’d attend after boot camp. Instead of “aircraft mechanic”, he ended up assigned to Aviation Electronics Technician training instead. About halfway through, the Navy realized he didn’t have the electronics background the rest of the class had. Candidates for training as “AEs” were required to have some college education on electronics theories of the day.

Suffice it to say that the Navy was none too pleased. They accused my father of fraud. In reality, it wasn’t fraud: it was ignorance.

But training AEs was expensive. And they’d already invested significant time in his training. They told him bluntly: if he didn’t finish in the top three, he’d be court-martialed.

He couldn’t rely on theory he didn’t know, so he treated every device as a black box. He fed in signals, watched what came out, and built his understanding from results instead of rules. He graduated near the top of his class, served twenty-four years, retired as a Chief, and eventually trained others at NamTra. The irony was that the “experts” were handicapped: the theories they’d memorized in the 1950s were partly wrong.

What he didn’t know was that he’d been dropped into the middle of a technological transition. In 1958, electronics was pivoting from the vacuum-tube world to solid-state transistors, and most of what the Navy still taught came from the tube era. The old formulas, the ones printed in the manuals, didn’t actually describe how the new gear behaved. His classmates had the wrong map; he had no map at all, so he learned by looking.

Their knowledge gave them confidence; my dad’s ignorance gave him clarity.

He couldn’t rely on theory he didn’t know, so he treated every device as a black box. He fed in signals, watched what came out, and learned what worked and what didn’t work through observation. Certain inputs produced certain outputs; he didn’t need to know why yet. It only mattered that it worked.

He graduated near the top of his class, served twenty-four years, retired as a Chief, and eventually trained others at NamTra.

The irony in his story was that the university-trained guys were at a disadvantage. Much of what they’d been taught in the 1950s was wrong. They carried confident but incorrect models; my dad, with no theory at all, built accurate empirical ones instead.

My dad didn’t know that he’d been dropped into the middle of a technological transition. In 1958, electronics was pivoting from vacuum tubes to transistors — in fact, I still remember watching him work on things with vacuum tubes; in television sets, I think — and most of what the Navy still taught came from the tube era. The formulas in the manuals didn’t describe how the new “electronics” gear actually behaved. His classmates had the wrong map; he had no map at all, so he learned by looking.

Watching him work that way stayed with me, though I didn’t realize it at the time. His success came from curiosity under pressure, learning to treating each circuit like a question or a puzzle instead of a lesson to memorize. Years later, when the Internet was starting to collide with the old phone-company world, I found myself in that same kind of uncertainty. Everyone spoke the language of expertise, but they weren’t all talking about the same thing. The network was changing faster than the manuals could keep up, and the only way to understand it was the way my father had: by asking what would happen if we just tried “this” and see what the system said back.

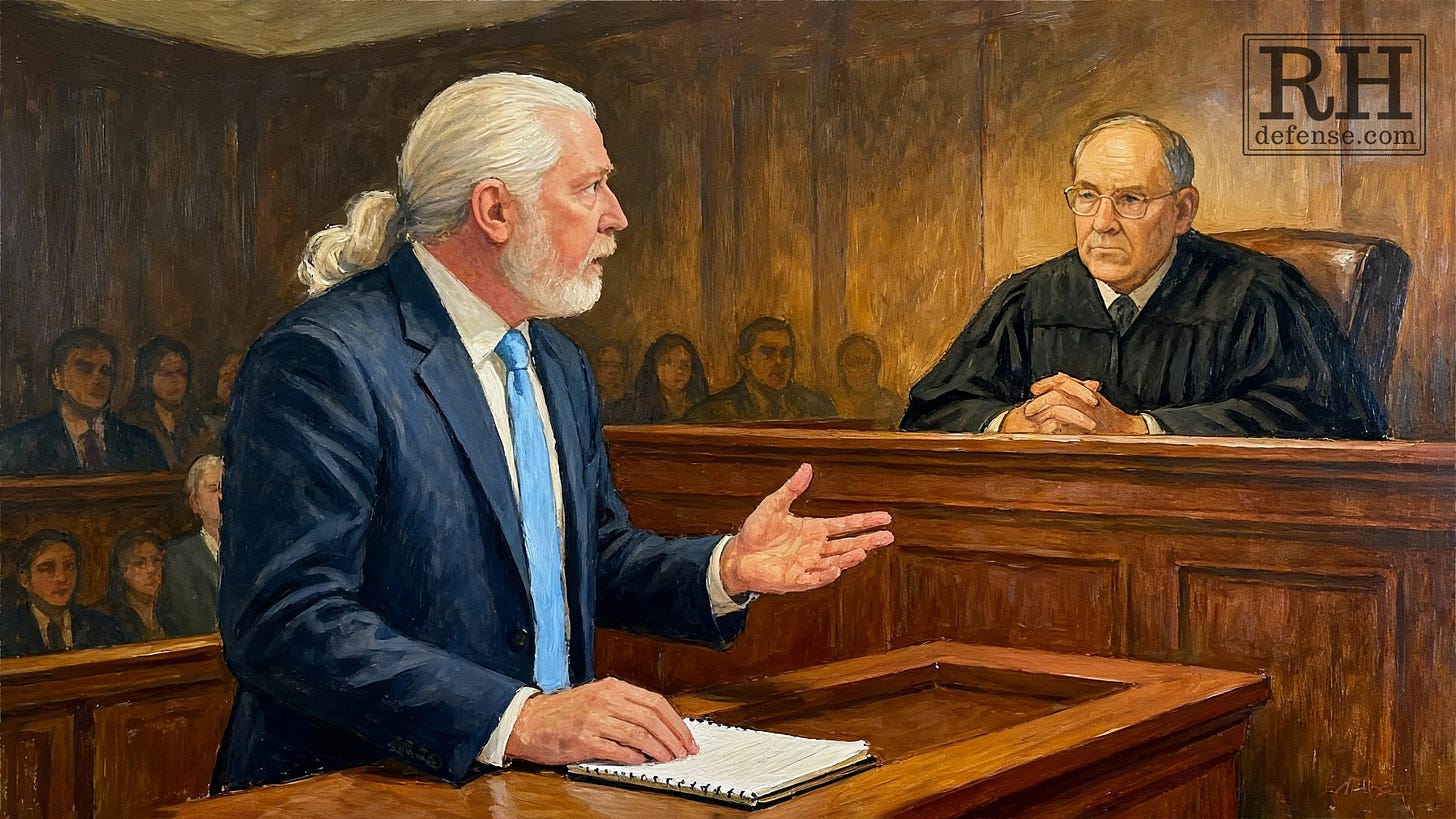

The Law’s Black Boxes

It’s a mindset I still use in court. The law has its own vacuum tubes. Stare decisis says we stick with old doctrines and habits that no longer match how the system really works. I approach a case the same way he approached a circuit: test the inputs, watch the outputs, and pay attention to what the experts overlook. Sometimes the black box isn’t a radar unit; it’s a courtroom.

Years ago, I was in Judge Penner’s courtroom. I had given a brief oral argument for why he should do a certain thing I wanted him to do. (It was years ago. I’m old. I don’t remember exactly what I was asking him to do.)

Judge Penner was not known as a sweetheart. I liked him, but I also knew to be careful with him. He wasn’t buying my argument. So I did what I often do in situations like that: I asked for more time. “Maybe I could brief it and we could come back and argue it after that?”

Judge Penner said, “Mr. Horowitz, I don’t see how you’re going to change my mind. But you’ve done it before, so I’ll give you the chance.”

When we left the courtroom, two much more experienced lawyers followed me out — one a respected private defense lawyer, the other a senior public defender named Eric Christensen. They told me they’d stayed just to watch the argument. Eric said he’d had somewhere else he needed to be, but couldn’t leave because he was fascinated by what I was saying. He asked, “How do you find such interesting cases?”

“They’re not interesting when they come to me,” I said.

And that’s the truth. Most of people walk into my office with cases that seem fairly routine. Same charges, same procedural mess, same presumption of guilt baked in before the paperwork dries.

But that’s the problem: when everything starts the same, unless you find a way to make it more interesting, then everything ends the same.

One step, then the next — until the box answers.

My job is to find the part everyone’s stopped looking at, the black box no one has opened yet. Don’t let the old theoretical approaches bog me down, producing an output neither my client, nor I, want.

Sometimes it’s a piece of evidence that doesn’t behave the way the prosecution assumes it should. Sometimes it’s a precedent that’s drifted so far from its purpose that it no longer fits the world we live in. Occasionally, it’s a reminder to court and counsel that they’re focusing on a minor blip and the law really intended something else — the thing my client and I want.

My “trick” for making cases interesting is the same one my father used for making things work. And the same one that got the Internet to work in the ’90s: keep asking questions until the system answers in a way that makes sense. Or, more accurately, until I get it to do what I want.

Along the way, the case becomes interesting. If I get things right, judges see things the way I see them. The black box — or, in this case, the black robe — produces the output we were looking for. And if I get things really right, everyone is happy with the result.

When you think about it, there are black boxes everywhere in life. Some we learn to open. Some we learn to talk to. Some we just learn to listen to.